In a special longform feature, Steve Carufel digs into gigs and listening data and speaks to the musicians involved to find out what has happened to Birmingham’s heavy metal legacy — and what might come next.

“Are you taking notes or recording? Because obviously, I’ll be going through a lot of stuff.”

This is how Steve and I started to discuss Birmingham‘s — and the West Midlands‘ — rock and heavy metal scene, then and now.

Steve Gould is a Birmingham-born presenter at Midlands Metalheads Radio, a producer, and founder of the young Fusion – Music Without Boundaries festival, which recently held its 2019 edition in Worcestershire. He has lived in the region ever since.

Even though none of us ever had any experience of the franchise, we decided to meet in a lousy Toby Carvery joint whose waiter came back two or three times to tell Gould they were out of what he wanted to eat — giving me plenty of time to ask him anything regarding the region’s music scene in 1972, 1984 or 2016.

As many people in the UK and elsewhere know, the region is, by most accounts, the birthplace of heavy metal music, starting with genre-fingerprinting acts like Black Sabbath and Judas Priest, half the members of Led Zeppelin, and later Diamond Head, Napalm Death and Godflesh.

But the region’s heavy metal expertise started centuries ago, literally.

Metal to the bone since… 1586?

During the late middle ages, if not before, the region grew an international reputation in metal trades and goods in the 16th and 17th centuries, burgeoning with smiths of all kinds through the city’s 200 forges: bladesmiths, goldsmiths, nailers, scythesmiths and locksmiths among others.

Britannia author William Camden wrote in 1586 that the region was “swarming with inhabitants, and echoing with the noise of the anvils, for here are great numbers of smiths and of other artificers in iron and steel, whose performances in that way are greatly admired both at home and abroad”.

Birmingham and the Black Country came to sit at the heart of the Industrial Revolution that would populate the place with heavy industries, along with their accompanying metal-pounding noise and coal-snowing clouds.

Some even suggest this harsh and dirty environment is what inspired J. R. R. Tolkien to come up with the Mordor and their covered-in-black, hard-working Orcs in The Lord of the Rings.

So in the ’50s and the ’60s factories and their workers came to dominate the city, and some buildings, long abandoned or alternatively used, can still be seen between Birmingham’s city centre and its northern part.

Birmingham born-and-bred Gould can testify to that:

“Obviously, it was more industrial back in the 1970s. You know, I think that’s where the term heavy metal comes from because there was a lot of forges, a lot of smog. There was lots of ironworks and foundries, it was very noisy. There was a very big steel industry in the Birmingham area.

“I think that permeated into the music, you know because it was like ‘BOOMF, BOOMF!’, you know the hammers going on and I think the music sort of came from this sort of heavy pounding, and you know Le[a]d Zeppelin, it was a very clever play of words. It was synonymous with the time it came out.”

But it’s 2019 now. 50 years after Black Sabbath had their first gig in 1969, are Birmingham and the West Midlands still metal to the bone?

In today’s highly digital environment with the availability of real-time data, it is increasingly easy to look up at cultural trends geographically.

Most scheduled gigs in a city are listed on one website or another, and some data-rich music streaming platforms are eager to let people dig into their data and find insights.

So Birmingham Eastside wanted to know whether data from concert listings and music streaming would tell us anything about the state of heavy metal music where it was born.

Is the region still metal, compared to other cities in the UK?

A quick look into Spotify‘s most-streamed music genres, helped by EveryNoise.com, tells us not only that heavy metal isn’t much of a thing in the city, but also that its closest parent, rock music, isn’t among the most popular genres either.

Particularly streamed music genres in UK cities on Spotify

Of course, Spotify’s music streaming data shouldn’t be considered reflective of a city’s artistic direction, as the platform is most popular among younger music enthusiasts.

But that is just the point of this data-digging: to see where the region may be headed in the future — the emerging trends — as those younger listeners will get older and as the platform will likely have more traction.

If anything, heavy metal music’s closest parent, rock, seems to be much more popular in Northern England and Scotland nowadays.

But let’s have a look at some concert listings data from Bandsintown which, conveniently for the concert-goer and the researcher, filter gigs by their (broad) music genres.

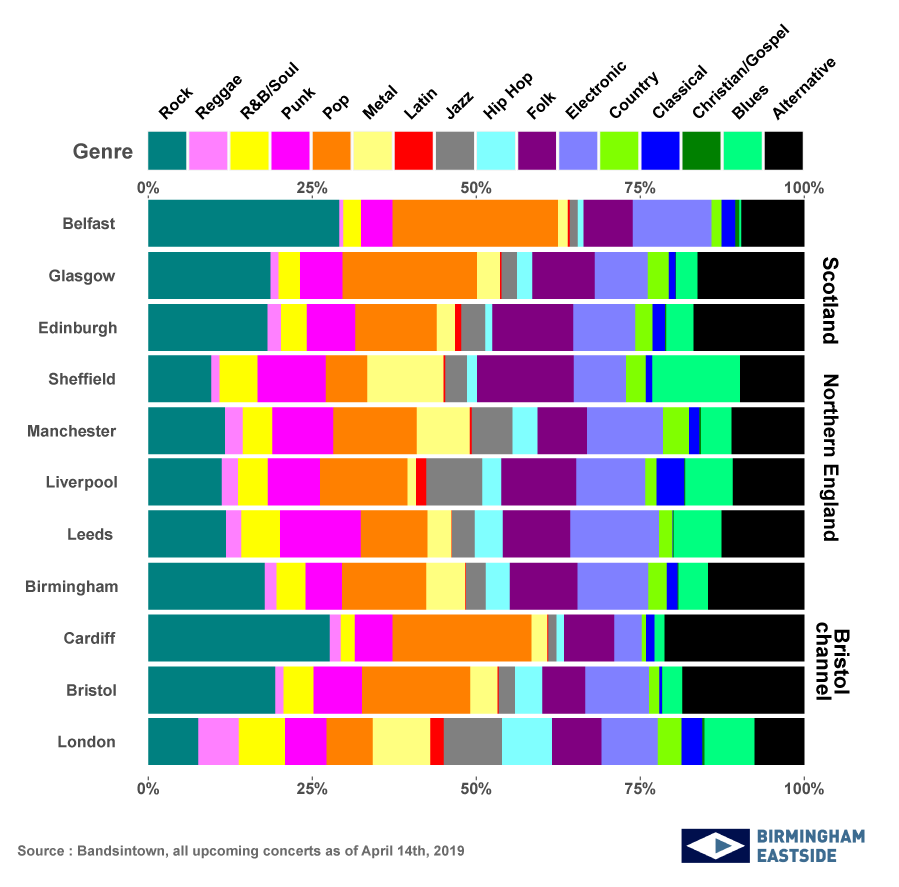

Music genres off all listed upcoming concerts on Bandsintown

The two Northern England cities of Sheffield and Bradford are where metal has a much thicker share of all listed concerts.

For the sake of coherence and confirmation, if we look at the genre’s closest allies, blues, rock, and punk, the North certainly stands out as well.

Punk gigs are particularly prominent in Leeds, Manchester, and Sheffield.

Blues is proportionally more prominent in Bradford, Liverpool, London, and Sheffield.

And finally, although confusingly, rock seems to be more of a thing in Belfast, Bristol, Cardiff, Glasgow, Edinburgh… and Birmingham, according to the data.

Some notes on the methodology: this concerts data does not take into account the size of a concert’s audience. A concert is a concert, regardless of the venue’s capacity, hence of the popularity of the artist and consequently the genre. In other words, a concert at the Arena Birmingham and one at The Hammer And The Anvil both equals one gig.

So there is, of course, some level of distortion. What’s more, when there is a festival coming into town soon, Bandsintown tends to list every or most playing artists as an individual event. But this latter may be actually a good thing for the data, as a festival is a much bigger thing anyway than a regular gig of two or three artists.

Which city has taken a lead in heavy metal?

I asked a few regional bands and music enthusiasts which other regions, if any, may have taken the lead in the genre — and it seems that one city does stand out, whether through the data above or in the point of view of local musicians.

“Sheffield”, simultaneously and immediately respond more than one member of local metal, post-hardcore band Failure Is An Option (FIAO).

“They’re all from Sheffield” adds Bran, FIAO’s heavy-voiced singer, about today’s modern metal bands.

“Sheffield is a very metal city”, agree members of A Titan, A Deity, another local metalcore band. “Northampton, maybe? There’s still Manchester?

“We do love the North [of England]. The North remembers!”

And for Wolverhampton-born At Dawn We Attack, who describe themselves as a “Hardcore Thrash Entertainment System”, it’s further north again.

Edinburgh, and Scotland more generally, were mentioned as having the best crowds by members of ADWA.

“In Edinburgh [they] were absolutely mental. We love the Scottish. We love the Scottish.”

So, what exactly happened to heavy metal music in the West Midlands?

It’s perhaps no surprise that the region may have moved on in the 50 years since the birth of heavy metal, as other sounds and cultural trends come and go.

And looking at what is particularly streamed on Spotify by Brummies, there are obvious demographical explanations as well.

Birmingham, for example, is the only city where desi, bhangra and punjabi and Indian music are part of the top 20 — even the top 10 in most cases.

But what would local bands say to someone claiming that Birmingham or the West Midlands aren’t metal anymore?

“Well just listen to the Pagans you motherf…” says Marius, the singer of The Pagans S.O.H., a band from West Bromwich that blends blues, rock, reggae, punk and metal music in their songs.

Other members of the Pagans S.O.H. have a more nuanced view:

“I think it’s a very niche market more than before… because everything now is more like house, rapping music. Some metal has gone a bit too far into the extreme stuff.”

They then refer to Black Sabbath, which isn’t anywhere near what they perceive as overly aggressive or heavy music.

“The very heavy and mostly the fast stuff, it doesn’t engage people as much as [something] quirky.”

And they are not sure the region has any particular metal identity at the moment.

“Lots of bands are trying to be like other bands, and they’re not trying to be original, so they sound like any other band.”

But others like At Dawn We Attack are quite content anyway with its current state, and the crowds it attracts at some gigs.

“It’s still prominent. There’s a lot of great bands coming out. There’s a lot of bands in Wolverhampton alone, surprisingly. It’s kind of thriving now because for a while it’s been Birmingham, Birmingham constantly.

“As much as people moan about ‘Oh the scene’s dying and all, […]’, well, there isn’t a ton of bands, you just gotta go and find them. The scene isn’t dying.”

“[Metal] is still there, but you kinda have to look for it these days”, says Luke from A Titan, A Deity.

“The quality of the shows still is really good for Birmingham, but having said that, it’s kinda split off in genres now, you used to get mixed bands together, now it’s more like hardcore has its own scene, metalcore has its own scene, and so on.”

“I’d say as an art form, I don’t think metal is dying, it’s just being a bit stale,” observes ADWA’s guitarist Benjamin. “It’s very much split between subgenres. And now there are like 30 subgenres of death metal when death metal was itself a subgenre before.

“Which is amazing if you think about it, because there’s so much to choose from…”

If Birmingham is headed in any particular direction in 2019 when it comes to music, my interviewees all name genres like grime, djent, trap and trap metal, but also metalcore, hardcore and even pop punk.

Notable named bands that are authoritative on those genres are Hacktivist, DVSR, 36 Crazyfists, Our Hollow, Our Home, and Bring Me The Horizon, although this latter has been described as much more “poppy” lately.

Locally, they are thinking about JayKae, Oceans Ate Alaska, and a trap metal rapper who goes by the name of Scarlxrd (pronounced “Scarlord”), probably the most intriguing, darkish and unique act the region, and maybe the whole country, has seen emerge recently.

Hello? Is it the crowd you’re looking for?

You probably can’t have metal music without its live audience either. Gig attendance is also an issue sometimes, for ADWA as with other bands. “Attendance can be bad sometimes, but more often than not, it’s a surprise to see [people turning up].

“And people go to Amazon to get a book rather than go to, like, a bookshop. I think it’s the apathy we said earlier, it’s like the digital age: it’s awkward.”

Other bands are no stranger to this challenge of getting people up and out of their homes and turning up to their gigs.

Venues have been closing. One that is widely appreciated by younger metalheads is The Flapper, which almost came to a close last summer but whose license ended up being renewed… for a year.

And this April, on its Facebook page, the venue announced it will be still good to go until January 2020.

It seems the venue has been struggling with its landlord fancying some other use for the land.

“[The scene] is going to die if they keep shutting down venues,” says Bran from Failure Is An Option. The band then refers to The Flapper as an “absolutely wicked venue” whose very existence is under pressure from “fat cat businessmen” trying to build properties there.

The venue also naturally comes to the minds of members of A Titan, A Diety. The first lease renewal announcement was “great news” for them, “but still in a year’s time it might be drying up.”

No such thing as Health & Safety… back then

Our veteran gig enthusiast Steve Gould also regrets the closing of venues, especially the smaller ones, “because you got more connection there than the big stuff.”

“A friend of mine recently said something clever: People can’t be asked, can’t be bothered to be apathetic. In other words, it’s too much trouble to be apathetic.”

It is in stark contrast to what Gould had the privilege to experience in the ’70s.

“I’ll be honest with you Steve. I get bored at gigs. I get bored at gigs now.”

He explains that, typically, too many bands just turn up and mostly play their album. “Might as well just listen to their album”.

“Genesis, Peter Gabriel used to dress up, like a foxy head and all those sorts of things. He just added that extra dimension. He put on a show.”

And some other bands, like Emerson, Lake & Palmer, were so ambitious on this matter that they literally shook the foundations of the Town Hall in the Birmingham city centre.

For their performance at the Town Hall in 1970, the band’s keyboardist Keith Emerson decided to take control of the venue’s colossal organ that wasn’t exactly meant for that.

“It didn’t go very well. What happened is that [the venue] found out a lot of the music they were playing was actually affecting the foundations, so for a long time, there were no gigs.

“It’s only been very recently, the last 5-6 years maybe, that they’ve actually started having concerts at the Town Hall again, from rock bands.”

As far as he knows, is that why the Town Hall decided to close the venue to rock bands for decades?

“Uh… I don’t think that helped. I don’t think.”

Decades ago, he explains, bands not only went at great lengths to entertain their audience, but the crowds themselves were also very much into the concerts they were attending.

And there was no such thing as Health & Safety.

“You know, if you wanted to get up and have a dance, and… freak out, then you could do that, you know, you would just do it. You hadn’t got to worry about some security guard jumping all over you. It was a lot less restrained then.”

“There was more of a synergy between the fans and the band, and because H&S wasn’t as obsessive as it is now, you felt freer, you felt a lot more freedom to be yourself.”

So, is there such a thing as a West Midlands heavy metal, or at least, musical identity in 2019?

The region’s fairly darkish or quirky identities have been a reality for a while now, and we can expect the city to again develop distinct identities, thanks to its unique ethnic and demographic changes, evident from the streamed music genres data. Cultural variation of a given genre alone has actually allowed whole new styles to emerge.

From the concerts data to the local bands’ point of view, the city is indeed onto something when it comes to rap, grime, trap, metal music and everything in between.

Carribean music mixed with electronic genres has been a thing for a while now. And during the 1990s, there was even what some named the “Birmingham sound”: a fast, brutally-repetitive king of underground electronic music, represented at best by Surgeon and Regis.

More recently, the local underground electronic music scene has been centred around the Listening Sessions, where emerging artists and producers have music listeners turn up in a bar to listen to their newly-produced music, quite an achievement in the digital age.

It is also around the LS that other music creation events are being held.

So yes, 50 years later, the region may have moved on from heavy metal, but only to take a taste of other trends and emerging sounds that will contribute to new music genres to come.

Leave a comment