This story can also be read on Medium here.

It is 4pm on a hot day in the state of Rajasthan, Northern India, on the other side of the screen. Champa Lal takes off the red scarf that serves as a face mask.

He speaks with a friendly and natural smile. He has grey hair and looks about 50 years old. The room is small, the door is open, and the light that filters through it illuminates his tanned skin and tired eyes. He speaks in Hindi.

Sudhir Katiyar, Director of the Prayer Centre for Labour Research and Action (PCLRA), will be the translator throughout the interview.

“I took an advance payment of 66 000 rupees (around £670) from the brick kiln owner. We used to make around 4000 bricks per day. They only paid us food expenses, but not regularly or in sufficient quantity.”

In 2018, he went to work in a brick kiln with his family. The brick kiln owner did not allow Champa Lal to visit his home and began to mistreat him when he asked for more money for food expenses.

When the season ended, the employer claimed an outstanding debt of 66,000 rupees (the same amount he had taken in advance).

“He told us we couldn’t leave unless we finished paying off that debt. We were left with no food.”

Champa Lal had his wife and five children with him. They were 15, 13, 12, 10 and 9 years old. All of them were working. Older children made bricks, and the younger ones did some other work like mixing sand.

“There are various positions that children can do in brick kilns. We would start working at 11 pm until 10 am. Then we would go to sleep. We would get up at 4 pm, and work again for three hours.”

Fourteen hours of work per day, working around the clock.

He managed to escape from the brick kiln, leaving his family behind, and approached Katiyar’s organisation, asking for help.

On 6th January 2018, his family was finally released from the brick kiln.

“I had to pay that money back or they would not let me or my family go home.”

Mukesh Chandra is young, he is in his thirties. He speaks slowly and with a serious countenance, wiping the sweat from his forehead from time to time. He was rescued in 2017 by the same union.

“I worked for the whole season — six months. I was promised 500 rupees (£5) for every 1000 bricks, and finally, when it was time to settle and pay the wages, the brick kiln owners said that there was an outstanding debt of 6000 rupees and that I had to pay that money back or they would not let me or my family go home.”

On 13 June 2017, Mukesh filed a complaint with the district magistrate. He demanded to be released from bondage and sent back home.

When he returned to the brick kiln that night, the employer beat him and left him injured.

He informed the union, which in turn informed the police. The next day, the police went to the brick kiln.

“They were drunk,” Mukesh said. The police beat him and took two of the workers to the police station, where they were forced to sign on a blank paper.”

Mukesh Chandra and his family were released from bonded labour in 2017. The union has complained to the authorities about the incident of police abuse, but no action has been taken to date.

8 million people living in modern slavery in India

Sudhir Katiyar, from PCLRA, explains that even though the law protects the workers and India has a progressive Constitution, the bureaucracy and the authorities favour the employer:

“The police and the bureaucracy often favour the richer class, the employers. But we also have very powerful legislation, and the laws favour the poor.

“Unfortunately, these laws are not implemented. Normally we are able to get the workers released, but the process is not smooth, and many abuses can occur as in this particular case.”

Around 23 million workers are employed in India’s 125,000 brick kilns. PCLRA, which is supported by Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiatives, and the Paul Hamlyn Foundation, helps Indian workers to access their rights.

Katiyar says:

“Workers in brick kilns and the farm sector are very poor, uneducated, and unaware of their rights. They work for very long hours and don’t earn proper wages, sometimes they don’t even get paid at all.

“Laws are not followed, and nobody has proper contracts. We try to organise them so they can access their rights.”

An estimated 8 million people are living in modern slavery in India. In brick kilns, debt bondage is the most common form of exploitation.

“Almost all workers in brick kilns are bonded,” says Katiyar. “They are paid in advance, so they don’t earn regular wages. They lose their freedom of movement.

“In most of the cases, the workers are normally in debt at the end of the work season, and the employer won’t let them go back. They don’t have the option of running away because their whole family is in there, children included.”

Paying workers at the end of the work season is also a very common phenomenon, not only in brick kilns but in other sectors as well.

“Workers go for 6–8 months to work in a particular sector, and they only get paid food expenses. The money is locked down with the employer, so the workers lose any power. They can’t go back to their villages unless the employer allows them.”

Katiyar said that most of the workers that file complaints end up going back to similar situations:

“There is no choice. Even those who are released, have to by force go back to work on brick kilns.

“There is no other employment available for them.”

Living conditions are poor and violence is very common.

“In many cases there is verbal and physical abuse. Workers live in small, low houses where they can’t even stand up, they have to bend down to get in. There is no decent drinking water, and often no electricity either.”

The caste system into which Indian society is divided prevents workers from organising to fight for their rights.

“The society is divided into thousands of castes,” says Katiyar, “and everything moves in the periphery of them: they are endogamic units.

“The working class is divided because of the caste system: Between brick kiln workers, for example, there are several castes, so that prevents them from being organised.

“The working-class form a very large section of the population, but they are uneducated, don’t have political power and are not organised. If they were educated, they would have a sense of entitlement and demand their rights.

“In public schools, there is no education taking place, on purpose. The power is held by a very narrow elite that ensures the perpetuation of hierarchy.

“Released workers who file a case are not going to change the system. Filing cases put pressure on employers, and the filing will provide temporary relief if you are in a very bad situation and you need to get out of it.

“But to change the system that is not the route. We need to organise the workers on a larger scale and put pressure on the employers and the government to ensure that laws are followed, and wages are paid decently.”

The UK Modern Slavery Act

India is the second-largest brick producer after China. These handmade bricks are used in walls, roofs, facades, garden landscaping or for paving roads.

How can we prevent bricks from modern slavery, debt bondage and child labour in India from being used by UK companies?

The UK Modern Slavery Act, introduced in 2015, requires UK registered companies with more than £36 million of turnover to publish an annual Modern Slavery Statement, setting out the steps taken to prevent and address modern slavery in their supply chains.

Kieran Guilbert, Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking Editor for the Thomson Reuters Foundation, said:

“The supply chains are increasingly globalised, complex and fragmented. We are talking of thousands, if not tens of thousands of suppliers in industries like technology and garment.

“I think it is hard to improve transparency when you don’t even understand your supply chain. As they don’t know the reality of their supply chain, how can they really effectively monitor it?”

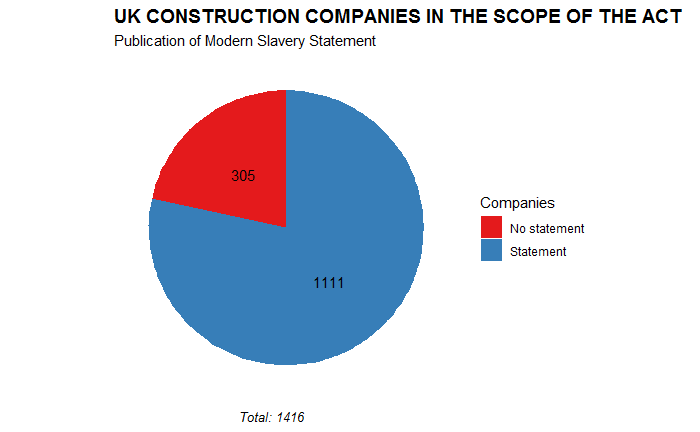

Out of over 1400 construction companies in the scope of the Act, 305 have not published a Modern Slavery Statement for any year.

And the proportion of companies failing to publish a statement last year rises to 40%.

Of the top 100 UK construction companies, 10 did not publish a statement in 2019.

Across all sectors, more than 18,000 UK registered companies are required to comply with the Modern Slavery Act. Of those, almost 4,000 haven’t published a statement.

Over 20 construction companies were approached for comment. None were willing to speak.

Why are companies not complying with the law?

Kieran Guilbert says companies are not complying with the Act because they don’t have to.

“It’s useless, there is no punishment for not publishing a statement.”

An Independent Review of the Modern Slavery Act last year concluded that the impact of Section 54, which sets out provisions on transparency in supply chains, has been limited to date.

It recommended that the Government should impose sanctions: from initial warnings and fines to court summons and directors’ disqualification.

Guilbert said that the fear that businesses would run away is behind the lack of penalties:

“The logic was that if you start with a punitive approach, businesses ‘won’t come to the table’. Companies are going to be too scared to look at their supply chain because they know that if they find modern slavery (which if they look properly, they are very likely to find) they will be found guilty and punished accordingly.

“In the UK with the Act there was a lot of push back from businesses, and there was a lot of disappointment on the other side, in the civil society, when there were no penalties for failure to comply.

“Companies can get hit by a big penalty for not following GDPA, but they are not going to be punished for having modern slavery.”

Even when companies publish a statement, it can be very vague and simply state that they are committed to tackling modern slavery in their supply chains, but without specifying any concrete measures.

Section 54(4)(b) of the Act even allows companies to report they have taken no steps to address modern slavery in their supply chains:

Kieran said:

“It is legally compliant for a company to just publish a statement on their web saying: ‘We haven’t found modern slavery.’ They don’t need to say what they have done.”

The Government and the future of the UK Modern Slavery Act

In response to a Freedom of Information Request, the Home Office said:

“The Home Office’s approach to organisations identified as not having published a statement is under active review.

“The Home Office is also considering potential future changes to section 54 of the Modern Slavery Act 2015.

“This follows the Home Office’s public consultation on transparency in supply chains, which was launched on 9 July 2019.

“The Government response to the consultation setting out our next steps will be published in due course.”

COVID-19 and its impact on modern slavery

The need for companies to investigate modern slavery in their supply chains is particularly critical during and after COVID-19, which is having and will have a strong impact on debt bondage, forced labour, child labour and other forms of exploitation, both in the UK and the rest of the world.

Kieran said:

“Anyone who is already in a situation of exploitation now is likely to be exploited more or they could lose that work and even seek more exploitative work or have to migrate.

“It might be so as well because so many industries are being hit, that either you lose your job, or your employer says: ‘We are now being squeezed by the big corporation in the West, if you want to keep your job you’re going to have to work double time for less pay.’”

He says coronavirus will also drive people who weren’t vulnerable or exploited into this vulnerability.

“Some of them will have to take out loans from local moneylenders to survive. How are they going to pay that off? They are not going to have work, so they are going to get trapped into debt bondage and work for the moneylender.

“On the other hand, what happens to people who are trapped in debt bondage now who can’t work to pay off their debts? Looking at the UK, what happened to the Eastern Europeans in car washes, the Vietnamese women in nail salons? They still must pay interest on their recruitment fees; they still probably have to pay their rent and other living costs.

“If they aren’t earning to pay that, those debts are going to increase, which will trap them in that situation for longer, or they are going to be forced to resort to other forms of exploitation.”

In India, COVID-19 has had a huge impact on poorer communities and increased debt bondage. Katiyar said:

“They have to earn wages daily to be able to feed themselves. They do not have any savings, social security or pensions. There is also an increase in cases of bonded labour and food shortages.

“We are receiving a lot of distress calls from workers. There have been calls of workers saying that they do not have food to eat, so we have got them rations of food, and they have also been calls from workers to be sent back to their homes. We have organised buses to send them back because there is no transport available.”

But Katiyar also thinks this could be an opportunity.

“There is a lot of focus on workers’ issues, it is a time of social upheaval, so I think it is the right time to push forward the workers’ movement.”

After being released, Mukesh has been working on brick kilns again, and is once again in debt bondage.

“It is my regular job, my occupation.”

During lockdown, the brick kiln owner gave him food expenses, but not for free.

“They were put against our names, so we had to pay it back at the end of the season.”

Champa Lal followed a different path.

“It was not a good experience, so I have never worked on brick kilns again”.

During lockdown, he used to work around his village breeding and feeding animals or harvesting. But now the situation has changed:

“There is no labour in our village anymore. Normally we would go and find work in some other village. Now that is not possible. It is a very tough time for us, we do not have enough food at home.”

* Read here an explainer about the difficulties of tackling modern slavery in the supply chains.

*The data on construction companies’ compliance has been obtained partly through web scraping. View the code and the process on GitHub.

Leave a comment