“It’s been really difficult being a city centre restaurant right in the heart of the financial district because there’s no one working here. It’s scary.”

For Ann Tonks, the managing director of Opus, the business impacts of Covid-19 have, like the pandemic itself, come in two waves.

In July, Opus announced that its bar, located within One Snowhill in Birmingham’s business district, would close permanently.

“It’s a site that is completely dependent on the businesses on the estate. No one’s working there at the moment, so it was not going to be able to reopen without some support on rent from the landlord,” says Ann.

Then, in early November, Opus’s fine dining restaurant closed as the UK went into a second national lockdown in response to surging cases of Covid-19.

Ann was hopeful that the restaurant would re-open again on December 3nd, but last week Matt Hancock, the Minister for Health, announced that Birmingham would move into the highest tier of regional restrictions, meaning that all bars and restaurants will remain closed.

“We need Christmas to make any money at all”

Keeping the doors closed over the festive period is particularly painful for Opus, which relies on increased demand near Christmas.

“We need December and Christmas to make any money at all. Our industry works on an incredibly low margin so you’re just trying to mitigate your loss for most of the year, rather than how much money you’re going to make.

“[In a normal year] at Christmas, there isn’t a service period where our private dining room isn’t full and we don’t have huge tables of business people in the restaurant.”

Ann said that private dining would normally represent 30% of Opus’s business – this year that element of the business has been non-existent due to restrictions on gatherings of people from different households.

But even after Christmas, it is possible that core elements of many city centre restaurants’ business models – business tourism, private dining, and busy lunch sittings – will not recover to pre-pandemic levels.

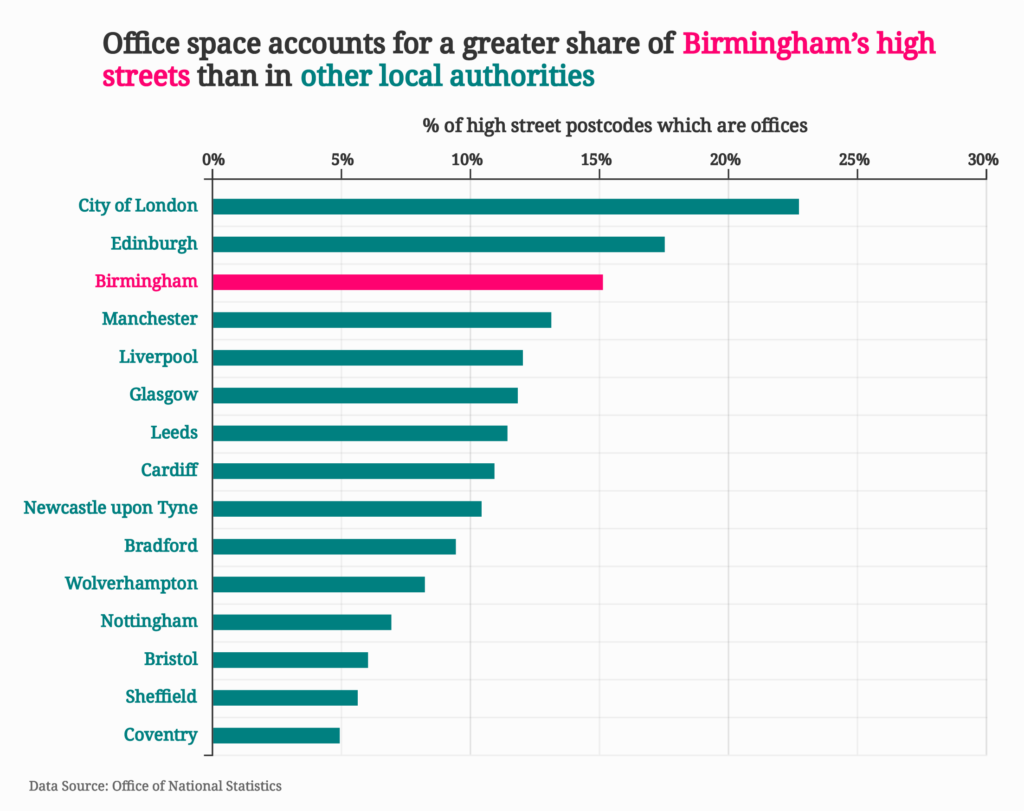

With many of the city’s largest businesses – including KPMG and HSBC – encouraging employees to work from home, office worker footfall in the city centre is currently just 12% of pre-lockdown levels, according to data from the Centre for Cities, a thinktank.

“I think there are patterns that are changed forever. I think it would be unrealistic to assume 100% of people return to offices even when it’s safe to,” says Ann. “What is the future of thriving city centres? That is a real worry to me.”

“We can never really compete with online”

Paul Lamb, the owner of Sims Footwear in the Great Western Arcade, is also worried about the future of the city centre.

“Nobody’s going to invest in office space like they used to. So the big picture, which is a bit scary, is what are our city centres used for?”

The pandemic has hit Birmingham’s retail sector hard. In July, John Lewis announced that their flagship store in Grand Central station, which only opened in 2015, would close permanently. Debenhams’s Bullring outlet is also due to close as the business enters liquidation, and there are fears for the future of Birmingham’s Primark store as the retailer’s parent company, Arcadia UK, went into administration on Monday.

Paul viewed the longevity of retail outlets in the city centre as an issue before lockdown but says that the pandemic has “fast forwarded ten years in the space of five months.”

“The problem has always been this imbalance between online and high street. We can never really compete with online because of our property costs.”

In February, 19% of all retail sales were conducted online, according to the Office of National Statistics. With non-essential shops closed, that share shot up to 33% in May.

There are concerns that online’s share of all retail sales could increase further during the Christmas period, and that bricks-and-mortar shops will not receive the boost in revenue that they need to survive.

These fears are partly due to the altered in-person retail experience this winter. With restaurants and bars closed, attractions like Birmingham’s German Christmas Market cancelled and the added risk of catching Covid-19, it may be difficult to persuade shoppers to visit the city centre’s retails outlets.

In a survey conducted by Springboard, a retail analytics company, 69% of shoppers said they intended to start Christmas shopping earlier to avoid congested shops. Such plans were thwarted by the November lockdown, which has created a constricted three-week period for purchasing gifts in-person.

Focused on survival

The pandemic is an existential threat for city centre businesses. In the latest survey of business impacts from the Office of National Statistics, 16% of retail and wholesale traders and 34% of the UK’s accommodation and food services businesses expressed little or no confidence that they would survive the next three months.

Ann at Opus talked about “finding a way to survive”, Paul from Sims Footwear says he is focused on “just getting through this as best we can and keeping on going.”

But Covid-19 has also stalled investment in city centres.

Fazenda, a small chain of South American restaurants, was planning to open their first establishment in London before the pandemic hit. But following the first lockdown, each of their existing restaurants – in Birmingham, Edinburgh, Leeds, Liverpool and Manchester – have at some point been subjected to strict local restrictions.

Plans for a London restaurant have now been postponed and Tomas Maunier, Fazenda’s managing director, anticipates the business will take two to three years to recover to its pre-pandemic position. He compares the business’s pandemic experience to “running a boat with no engine and no fuel.”

Like Opus, Fazenda relies on footfall from local offices and a jump in corporate demand in the run up to Christmas.

“There’s nothing that we do today that will be able to offset this four weeks of lockdown and December is usually about 15% of our annual turnover. It’s a massive amount.

“[Office worker footfall] has been really reduced, and that automatically has a massive impact to our business because we lost all the lunch trade during the week.”

“Doing more, paying the biggest costs”

Tomas believes that the closure of non-essential businesses during this second wave of the pandemic has been unnecessary.

He says that Fazenda “went the extra mile” in reorganising their kitchens, adapting the way their service staff interact and reducing capacity to ensure that their customers were safe. As a result, Tomas claims that only eight of his 330 employees have tested positive for Covid-19, with a further four reported cases among customers.

“I’ve been to the supermarkets and no one asks you to sanitise your hands on entrance. I’ve seen people not wearing masks. So the reality is that our industry has been doing more than anybody else and yet it’s paying the biggest costs.”

An assessment by the UK Government’s Scientific Advisory Group (SAGE), published in October, said that the closure of non-essential retail had a “very minimal impact on R values.” The report also said that the closure of bars, pubs and restaurants had a “moderate impact” on transmission, with an estimated reduction in the R number of 0.1-0.2.

The guidance, combined with pressure from UK retailers, appears to have influenced government policy on non-essential retail: shops will now stay open even in regions in the highest tier of restrictions. However, restaurants will remain closed in the top tier.

In a separate report, SAGE advised against the 10pm curfew on pubs and restaurants – a policy that badly impacted Birmingham restaurants.

“The curfew was very detrimental to our business. It dropped another 20% on our sales because we pretty much lost a full sitting,” says Tomas.

Ann described the curfew as “sudden” and “ill-thought through” and felt that government policy overall had been “very knee-jerk.”

Uncertainty around curfews and the tier system coming out of the November lockdown has made it difficult for businesses to think ahead according to Ben Brittain, a policy analyst at the City Region Economic and Development Institute (City-REDI) at Birmingham University.

“If you’re a small business owner of a restaurant, for example, you can’t take bookings, you can’t order the food that you will need and decide what to do about staff.”

“No way on Earth we can pay business rates in April”

But it is longer-term planning that is proving most challenging for businesses in Birmingham’s business district. With uncertainty around how quickly and in what volume workers will return to offices, many businesses are stuck in strategic limbo – waiting for a clearer indication of how the Government plans to support the retail and hospitality sectors during the recovery.

Paul says Sims Footwear “will need ongoing supporting or it will be impossible.”

“Now we’re realising that it’s going to go on for a long, long time before we get – if we ever get – to what things used to be like.”

Paul thinks reforming the business rates system, which he describes as “not fit for purpose”, should be a government priority.

“It’s crazy. We’re paying quite a significant tax – which I don’t think [shops] mind doing if we’re making any profits but if we’re losing money…so the business rates system needs a massive remodel. And this has been said for 10 to 15 years.”

In March, Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced 12 months of business rate relief for all retail and hospitality businesses. Revo, a professional body representing landlords and retailers, has called on the government to extend 50% of that relief to the 21/22 financial year to “prevent a cliff-edge in April.”

Ann says that unless recovery is surprising fast, there is “no way on Earth” that Opus will be able to pay business rates from April.

“We can only return to a normal business model when we have full capacity of offices around here and it doesn’t look like that’s going to happen anytime soon.

“We would also appreciate a continuation of VAT at 5% and flexible furlough for as long as that could conceivably go on.

“And I think, if your business has no possibility, because of where you’re located, of returning to X per cent of normal then I think some targeted support would be really helpful.”

Tomas is most concerned about rents, which account for about 10% of Fazenda’s expenditure.

Businesses that cannot afford to pay rent are currently protected by a moratorium on evictions. But that policy is due to expire on December 31st, raising concerns of a foreclosure timebomb as struggling businesses are suddenly expected to pay months of rent at once.

“The moratorium is a joke, because all we’re doing is building up a big bill that from the 1st of January, we have to grab our chequebooks and pay it in one go,” says Tomas.

Saving Birmingham’s city centre

Ben Brittain thinks that government support should be flexible:

“[Spending] needs to be evidence driven and regionally driven. The make-up of regional economies are completely differently, so support that works for Liverpool may not work for the West Midlands. So it has to be tailored and the regions have to have a larger say on that recovery.”

A targeted approach would be particularly beneficial to Birmingham’s city centre businesses, which could claim to have greater long-term viability than shops on declining high streets.

Providing additional support to businesses with promising long-term prospects could also ensure that investment in the city centre continues in preparation for the Commonwealth Games in 2022.

Ben warns that the pandemic could leave “long-lasting scarring” on towns with declining high streets like Sandwell and Walsall, but is “more optimistic” about the future of Birmingham city centre.

“It’s entirely linked to disposable income and demand. One of the reasons Birmingham has Michelin star restaurants is business tourism. You get high-wealth clients coming to visit for conferences, staying in hotels and going to fancy restaurants. Now that you can’t go to conferences and businesses are operating from home, there is not that demand.

“That will return – there might be a hybrid way in which workers work from home – but many will return. So the pandemic is hitting hardest in the areas that will also bounce back strongest.”

“People will smile again”

Through challenging times, Ann has found her own reasons for optimism:

“[Our local suppliers] have an incredible ability to be positive and find new ways of working. [Our employees] could hardly wait to get back and engage with customers, and then the customers have been phenomenal. And it gives you a real faith in that sense of a connected community.”

Tomas has also seen community and solidarity strengthen during the pandemic:

“This is the first time I have seen massive groups of people, businesses and communities really relying on each other. [Before the pandemic] a lot of businesses only cared about profits. Now they realise that they need to care about their team.”

And Tomas is hopeful as he looks ahead to the hospitality industry’s recovery:

“We are social animals and here in the UK – we love going out, spending time with friends and family. This is who we are. I am positive that people will support our industry.

“Our industry is about making other people feel special. It’s totally reliant on smiles. And I think people will smile again, and our business will too.”