Home care worker numbers have been dropping in Birmingham since 2010 — and the cries of protest are only getting louder. Hugo Barbieux investigates.

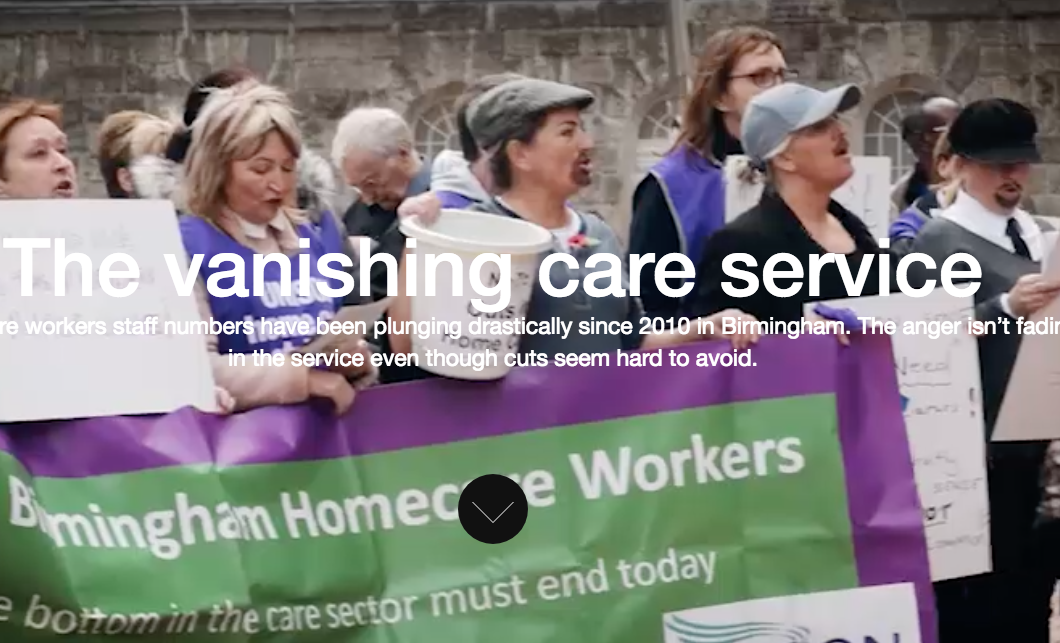

Home Care Workers demonstrate in front of the City Council

Rallying against the cuts

“We don’t work for pin money”

Chant by care home workers marching against job cuts

The British health sector is seen by the rest of Europe as one of the most efficient and egalitarian on the continent. But health services in the UK are facing a mounting crisis, especially those provided by local authorities.

Birmingham is no exception: a report by Birmingham Health Directorate (PDF) acknowledges that “the challenges facing the city council have never been greater.”

In addition to historical cuts, the city council anticipates making further cuts of £123 million by 2021/22 and the adult social care service will suffer cuts unlike any other branch.

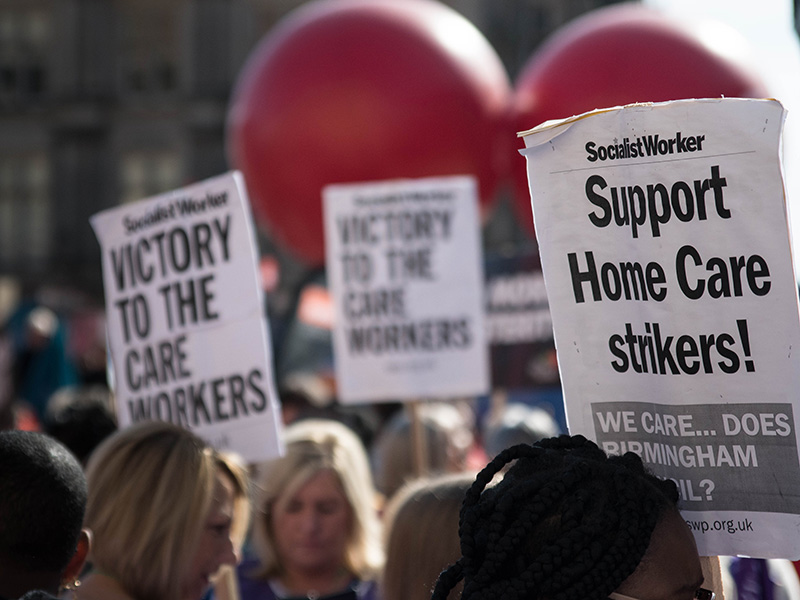

Care workers on strike

On a sunny but cold day of early November, a group of employees took their lunch-break on Victoria Square, in front of the council. They were enjoying the sunlight when the peace was broken by several women singing to a war song rhythm.

Home care workers were on strike, seeking to make their voices heard by councillors.

Following the stairs leading up to the square in a cavalry-like move, they progressed in a large pack holding banners. Some dressed up with beards, ties and jackets to convey the message that high wages are a man’s privilege.

The city council announced additional cuts to the budget in July and home care workers have rallied many times since. Part of the cuts include lighter shifts for employees, meaning pay cuts for employees. The service has been on strike for 32 days of the year so far.

On this day in November, the protestors were satisfied with their protest because they entered the council during a live session: no one present could have failed to be aware of what care workers were willing to do to defend their jobs.

Austerity from London

But are Birmingham’s councillors to blame? Much of the budget of the local authority comes from national government grants — and since London turned off the tap in 2010 as part of its austerity programme, Birmingham has had to deal with significant cuts.

Boards in support of the Adult Enablement Care Service

“We used to have a really big home care service, it’s all gone”

Caroline Johnson, branch secretary at Unison

Adult social care services are a strategic part of a city council’s mission to serve the ageing population; people live longer and therefore often need more assistance.

The population aged 65 and over from 2017 to 2035 is projected to increase from 10 million to 14.5 million people in England according to Skills For Care.

The same organisation estimates that an increase of 40% in the workforce is needed to accompany the rise of the ageing population.

In Birmingham, however, the public sector is shrinking, not expanding, with adult care services increasingly left in the hands of the private sector.

And Birmingham is not the exception. In every local authority, the private sector employs an overwhelmingly higher number of employees than the public sector.

Caroline Johnson, branch secretary at Unison, says:

“We used to have 45 elderly residential homes in the city provided by the council. We used to have a really big home care service with 1,100 workers providing everyday home care — and it’s all gone.”

As the biggest council in the country, Birmingham remains the local authority that spends the most on adult social care. But it also faces some of the biggest challenges.

10,815 people over 65 in the authority suffer with dementia. A report from the council’s Adult Social Care Directorate says: “There are significant numbers of young adults who have disabilities or suffer from mental illness.”

The city is younger than others, however: people aged between 18 and 64 represent 61% of the population and the figure is predicted to have risen by 8% by 2035.

On the other hand, in a report called “How are we doing”, the city council is ranked 15th out of 16 similar local authorities when it comes to the performance of adult social care services.

Talking about prevention while spending more on treatment

The city council has publicly said it is adopting a preventive strategy, saying that it aims to develop tools and equipment to ease the lives of people who face difficulties in order to help make them more independent.

This would mean that people need less medical assistance, easing the strain on the NHS.

The strategy has been developed by Dr Graeme Betts, who became the Director for Adult Care and Health in 2017 on an interim basis.

But spending data contradicts the public claims about focusing on prevention: Birmingham spending on prevention and early intervention in 2017-18 was lower than the previous year, while spending on treatment has increased. And overall, prevention continues to represent a small amount compared to care activities.

Meanwhile the budget for the financial year 2018-19 shows that Corporate Director service expenditure shot up 75%, from £9.7m to almost £17m — despite the management team overseeing a service which now ranks 151st out of 152 local authorities.

No comment from the council

Despite numerous attempts to reach the city council, no one responded to our telephone and email requests for comment. Both Dr Graeme Betts and Cllr Paulette Hamilton have refused all requests for an interview.

Among care workers, only Caroline Johnson was allowed to speak publicly to journalists.

Listen to the audio story to understand more about the situation of care services in Birmingham.

Note: this story is published under open journalism principles, which means the author allows anyone to read the data and the analysis undertaken.

You will find the data on this GitHub file. Follow the link to access the data.

Calculations have been made using RStudio. In order to look at the analysing process, first download R Studio from here and follow this tutorial.

You may also find the original and interactive version of the story here.