Over the last decade the EU has spent over €118m on checking the figures on development cooperation projects. But most of that money has gone to just a handful of accountancy firms. In a special investigation including never-before-seen data, Hugo Barbieux looks at how the ‘Big Four’ accountancy firms have come to dominate the field — along with a fifth: Moore Stephens — and why this has raised fears about lobbying to shape tax legislation that benefits corporate interests.

For the European Union, helping developing countries is a duty. The union has been financing development cooperation projects for decades, through a variety of means.

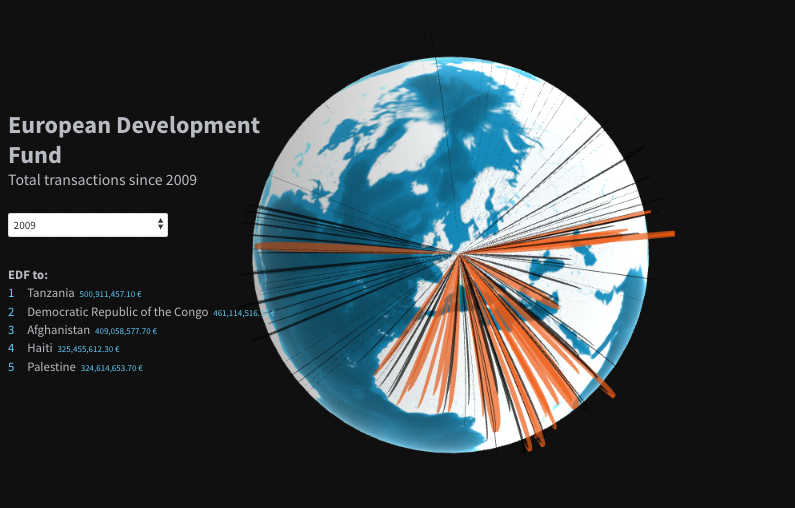

The primary money pot sits outside the actual EU budget, and it’s called the European Development Fund (EDF).

Like the EU budget, the EDF is financed with contributions from EU member countries — and for the period of 2014 to 2020, the EDF is worth over 30 billion euros.

“The industry has changed so much”

Fifty years ago, Eugene Rausch made it his job to help Africa. But it was more than a job, it was his passion.

It was the reason this 74-year-old Belgian-Luxembourg auditor entered the engineering industry.

“I wanted to see the world” says Mr. Rausch.

“I worked within European delegations and then I became self-employed. I have worked for agencies in Germany or Luxembourg but mainly for the European commission, which delegations regarded highly”.

Mr. Rausch climbed the ranks of the audit industry:

“I wasn’t earning a lot of money, especially when I compare with my colleagues who were engineers in Luxembourg. They embraced great careers, but the industry has changed so much”.

The good-old-days tone of Mr. Rausch’s words tell a story that seems far behind us. Today, the audit sector is very institutionalised and governed by complex schemes under international agreements. The framework in which development cooperation audits stand is the “Cotonou agreement”.

European sources say “DG DEVCO (the directorate general to development cooperation) has an efficient and effective system in place to contract audit-related services for 600 to 700 project audits per year”.

The Big Four — and a fifth

Financial auditing is dominated by four main companies. You have probably heard of the “Big Four” — Deloitte, Ernst&Young (E&Y), KPMG and Price Waterhouse Coopers (PwC).

Their presence is worldwide. They rose when smaller companies merged, and they have become ubiquitous in the private sector as a result.

Some 64 per cent of FTSE100 finance directors are linked to the big four accounting firms. This begs the question, have they become too big? Are they too greedy?

Public records, put together for the first time for this story, show just how lucrative the business of auditing EDF development cooperation projects is for these four accountancy firms — along with a fifth called Moore Stephens.

From January 2009 to August 2019, the records show that more than 7,500 audit-related contracts have been issued by the EU.

Nearly half the contracts went to one of these five companies.

DG DEVCO denies favouring any firm. It says:

“4,766 contracts worth €146 million were awarded for audit-related services, of which 2,061 contracts worth €61 million were contracted with the “Big Four” (42%)”.

The European Commission hasn’t shared its calculation methodology or documentation, so it is not possible to verify those figures.

And although the EU’s reported rate of 42% remains a high rate of audit-related contracts going to the “Big Four”, public data reveals quite different figures.

The “Big Four” were awarded 63 million euros’ worth of contracts (55%) over ten years. The rest, €55.5 million, went to other firms.

But it doesn’t mean smaller enterprises share half of the pie. Data show there’s a fifth big actor in the European game: Moore Stephens alone earned nearly 33 million euros over the past 10 years.

Contacted about those figures, Johan Van Mieghem, the man responsible for audits at Moore Stephens Belgium, said they wouldn’t provide any comment.

“The role of the “Big Four” seems to be quite substantial within the EU policy making process”

In a report on lobbying by big accounting firms, the NGO Corporate Europe wrote that the “Big Four” and European Commission share both a common culture, and personnel.

Over time, this has allowed the corporations to shape tax legislation that benefits corporate interests, and use lobbying manoeuvres to get the best opportunities.

Vicky Cann, campaigner for Corporate Europe Observatory says:

“We see that the “Big Four” is picking up consultancy contracts paid by the Commission including on issues where they have a commercial interest.

“When you add that to the role that members of the “Big Four” play on informal, voluntary, advisory or expert groups, on acts about tax avoidance, we can say that this role seems to be quite substantial within the EU policy making process”.

After the crisis

Concerns have increased in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. As a result of that crisis, tighter legislation was passed in 2014. A rotation system is in place under DEVCO’s audit framework contract system. All framework contract providers are equally invited to present offers for specific requests for services. This rule is supposed to guarantee an independent audit.

It’s difficult to say whether the deeply-rooted web that the “Big Four” have in European institutions actually helps them get privileged contracts. Previous scandals make it reasonable to wonder if that legislation has been influenced by lobbyists.

An EU source denies this, saying:

“The Commission evaluates the financial offer, as well as the technical quality of the offer.

“Expertise in EU policy areas, ability to regularly and rapidly submit offers and compose audit teams at short notice, may have an influence on the quality of offers and a realistic estimation of costs.”

A source in DEVCO also says there is a strict conflict of interest clause in all contracts and contract award procedures, and the European Court of Auditors annually audits DEVCO’s accounts and systems.

But experts say this legislation doesn’t provide enough guarantees, and there is still a risk that audits lie in the hands of just a few actors.

Prem Sikka is a professor of accounting and finance at the University of Sheffield. He says: “The EU rotation and tendering rules meant that the same firm could remain in office for up to 20 years.

“If new players put in a bid, which could have a heavy financial cost, and failed, they would receive no return from that investment and experience because they will have to wait another 20 years before bidding again.

“The policy is not conducive to increasing choice and competition.”

In other words, smaller enterprises with less personnel take on more risks when they pursue bigger audit projects, especially if they fail to get profitable contracts.

Unforgiving consequences

Failing in the audit industry can have unforgiving consequences. Audit procedures are timed, and timings are tight. According to Mr. Sikka, completing more audits is more important than executing clean audits.

“Quality inspections show that many major firms fail to meet them. Audits are generally labour intensive and within firms there are pressures to increase profits. Individuals are subjected to performance appraisals and often their promotion and financial rewards depend on contribution to profits.”

An employee of a big accounting firm, who wished to remain anonymous, confirms there are pressures to finish an audit mission in time.

He says: “If you think that your mission will take twenty days but then in the meantime you see unexpected issues in the company accounts, [you know] it will take more time and therefore will create additional costs to the auditor.

“So, we have quality checks to meet but it happens that we go too fast to complete them. We never botch the job, but it happens to speed up the pace.”

This race to profits is a losing battle for smaller actors. The legislation enforces quality standards and strengthens action against fraud. But the most powerful companies have though more levees to diversify their activities and to enhance their profits.

“I understand smaller firms’ concerns” says the same anonymous source. “The audit industry has reached maturity. Now enterprises need to be audited, and it is logical to find other services to propose to our clients”.

“Big audit societies are no longer strictly financial accounting firms,” says Mr. Rausch, who will retire in a couple of months.

“They need to do more and more technical audits, and so they buy experts here and there. It has become a real problem.

“At the very beginning, when the EDF was created, every country had a share. When we were looking for consulting experts for developing countries, we tried to respect quotas. For example, we were looking for two or three experts in Luxembourg. We told countries where to find the expertise they needed”.

Smaller firms complain that international agreements encourage a tougher competition they simply can’t bear. Mr. Rausch agrees:

“Today, agencies like mine have no chance to survive and no one I know in my firm is able to do that job”.

Leave a comment